Around the world today, aircraft are being guided around the skies by air traffic controllers. Each controller is responsible for a sector, keeping aircraft safe by talking directly with pilots using radio communications. Estimates show that the growth of commercial air traffic is already exceeding the capacity of a human-centered system — and that is only for human-piloted flights. The expected growth of unmanned and self-piloted operations will increase traffic by several orders of magnitude.

To handle this dramatic growth, air traffic management must shift to a more scalable model: a digital system that can monitor and manage this increased activity. That system is what we call Unmanned Traffic Management, or UTM. The UTM team at Airbus has spent months executing research and tests to determine our recommendations on the best approach for a future UTM.

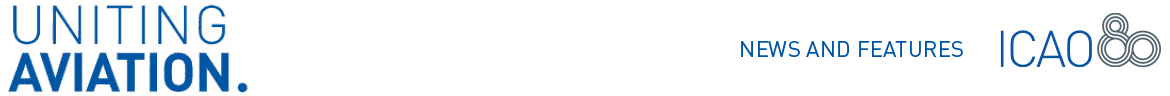

UTM is not a single, central system that mandates one way of operating for everything. Instead, it is a framework. It is a networked collection of services that join together and understand each other, based on common rules.

UTM is built to enable future applications. The challenge is designing a system that can remain relevant as technology progresses and market needs mature without knowing what that future will look like. For example, look at this ecosystem where all different type of aircraft serve communities through new missions and flight profiles such as self-piloted media drones, blood delivery, emergency services, and passenger delivery.

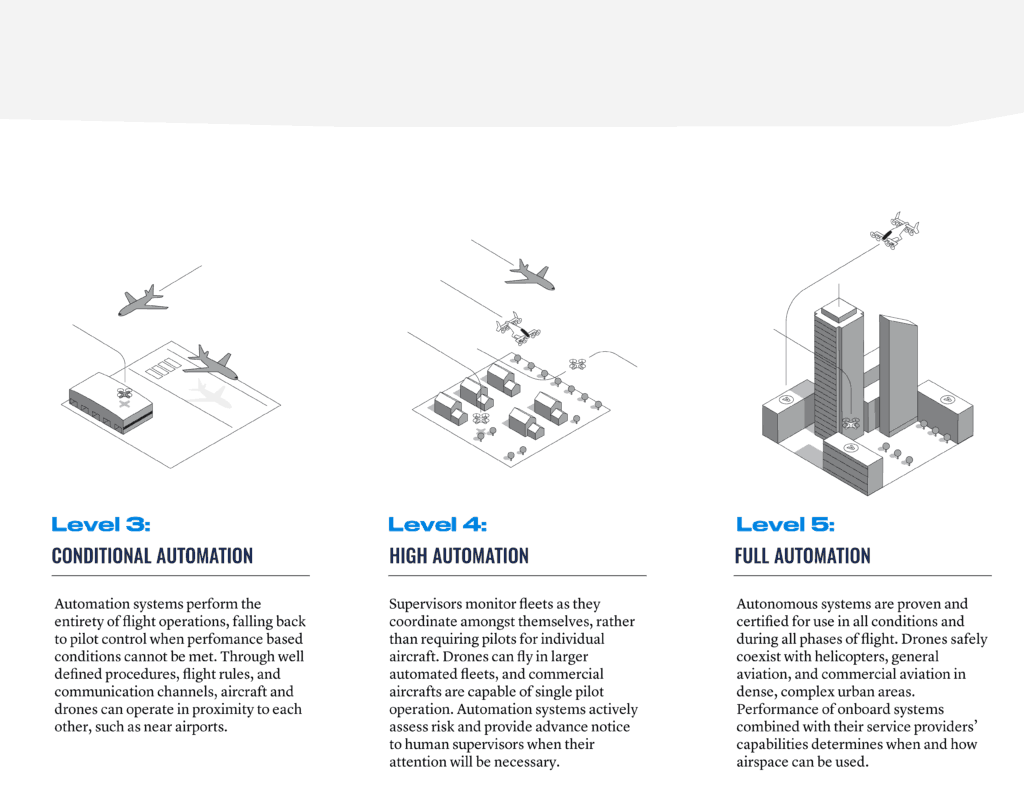

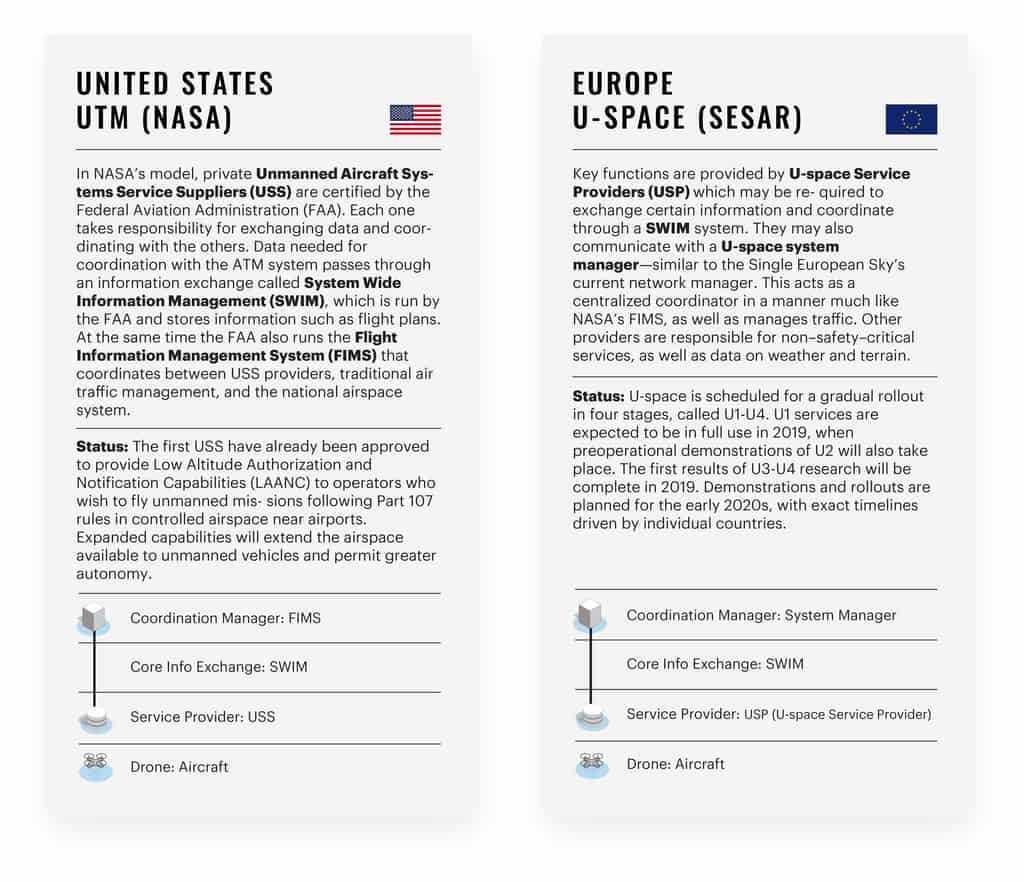

Rather than relying on centralized control, UTM frameworks around the world use the principle of distributed authority. This opens up the system to more service providers, who can adapt as the market evolves and needs change. Decentralization privatizes the cost of serving and adapting to market needs, while government regulators remain key for ensuring that safety, access, and equity are maintained.

In practice, this means aircraft are no longer forced to talk only to a single entity, such as an assigned air traffic controller. Instead, aircraft can communicate freely with their service suppliers of choice, who are held to relevant safety, security, and performance standards by the authorities and coordinate with the rest of the network to make efficient decisions based on specific flight objectives.

Human air traffic controllers, meanwhile, will become airspace managers, focused on oversight, safety, and security.

UTM allows the same foundation to serve different needs in different geographies at different times. Regulators can adapt requirements to match their local needs, and operators can select the providers they need to complete their missions. Providers can create, update and deploy their own services quickly. One operator can choose to build, certify and supply its own services, while another may find the same services in a marketplace. Providers will be responsible for coordinating with each other.

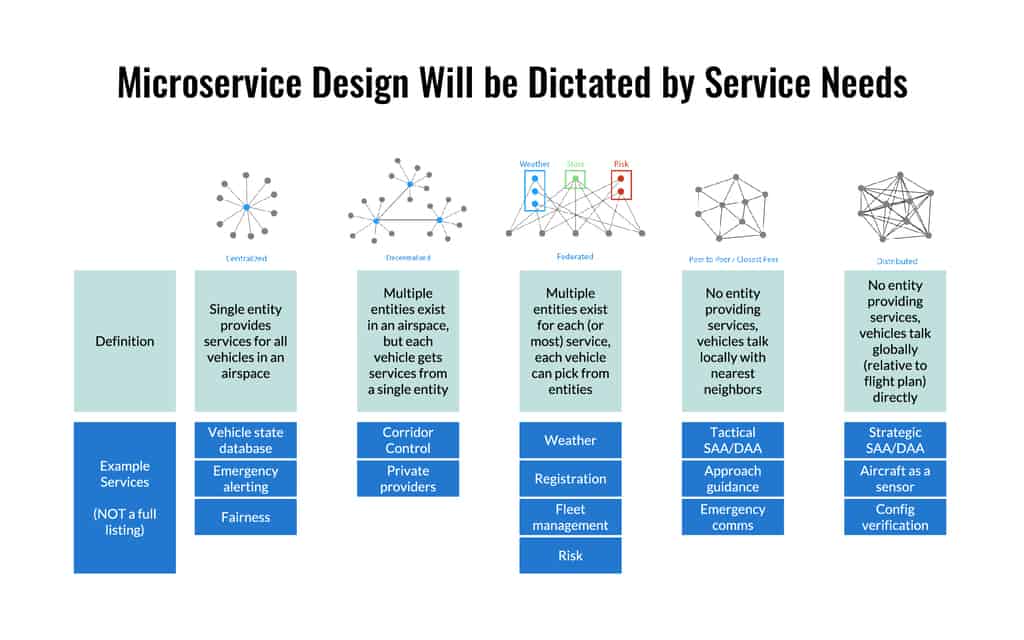

For unmanned applications to thrive, many stakeholders must come together to advance their respective domains. Advances can be accomplished in phases, with each phase dependent on the previous ones. As UTM shows positive results, there may be technology sharing or increased integration with traditional ATM.

Several countries and trans-national bodies have already adopted this overall approach as the foundation for their own UTM implementations. Each government has a slightly different view on how authority should be distributed. We believe ICAO has an important role in the support and development of future traffic management systems, particularly in supporting the ecosystem to adopt safe, efficient, and secure harmonized architectures.

The digital age of aviation will revolutionize flight. With its Blueprint for the Sky, Airbus has outlined a roadmap integrating autonomous aircraft and welcoming a new era of aviation – safely, efficiently and fairly.

![]()

Jessie Mooberry, Head of Deployment at Airbus UTM, is dedicated to bringing together policymakers, technologists, and NGOs to modernize air traffic management.

She is a technologist at the Peace Innovation Lab at Stanford and started her UAV career, with Uplift Aeronautics, building fixed-wing aircraft out of a garage in Stanford with the world’s first humanitarian drone cargo nonprofit. Jessie was one of the first to obtain a commercial drone license in the U.S. She is a Social Enterprise Fellow and Mentor for the Ariane de Rothschild Foundation. In addition, she sits on the Boards of People’s Light and WeRobotics.

Opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and may not reflect the opinions of ICAO or it’s Member States.